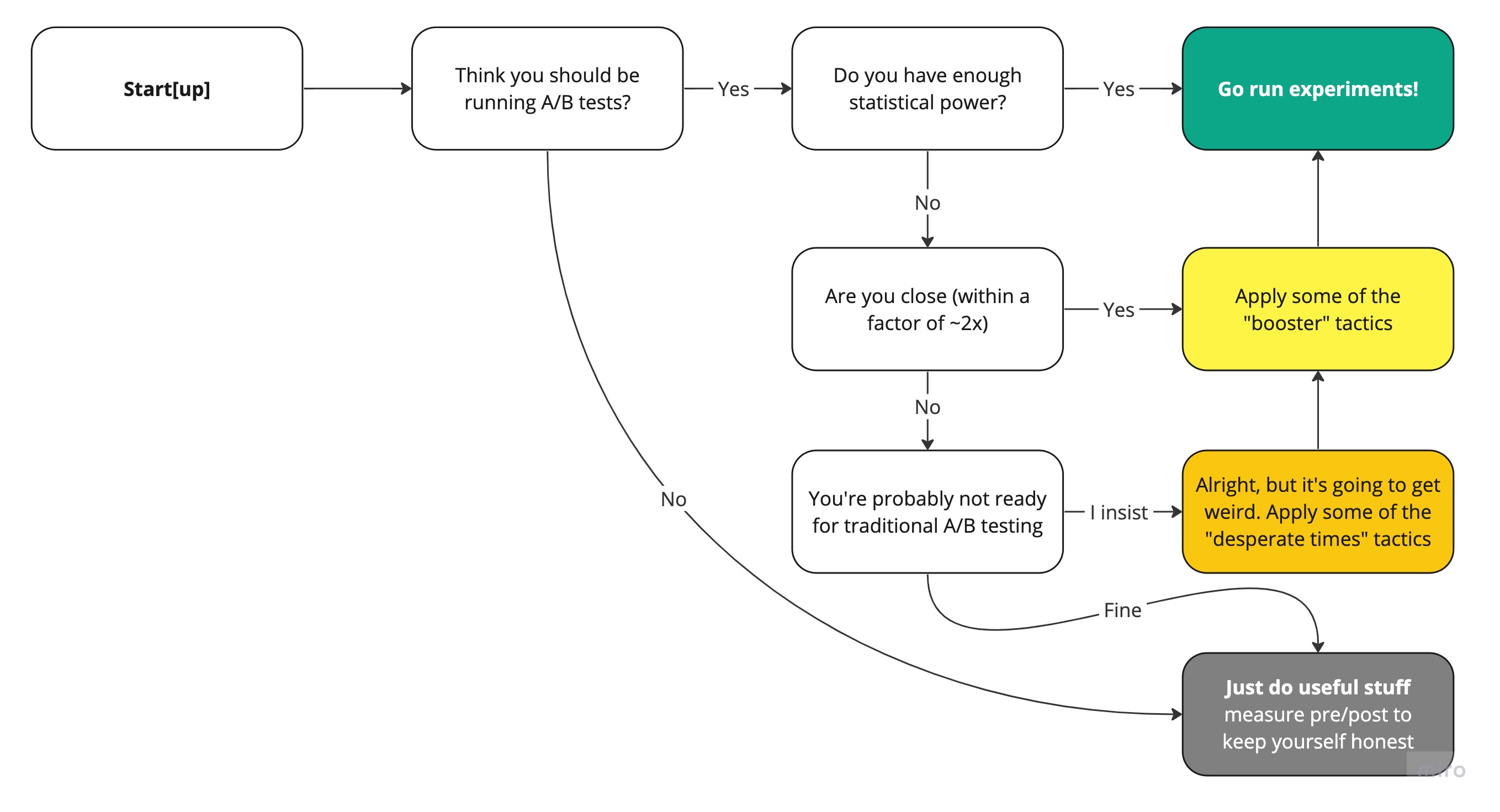

Many startups experience a chicken-and-egg problem with growth: they want to run experiments to gain more volume, but lack the volume for experiments to be practical.

This guide helps companies determine if (and how) they could staff a Growth team to start running experiments. First, we’ll diagnose what is achievable with the amount of traffic currently available. Then, we’ll dig into what techniques might be available to increase experimental power.

As any proper guide ought to, this one includes a handy flowchart.

Part 1: Do we have the numbers?

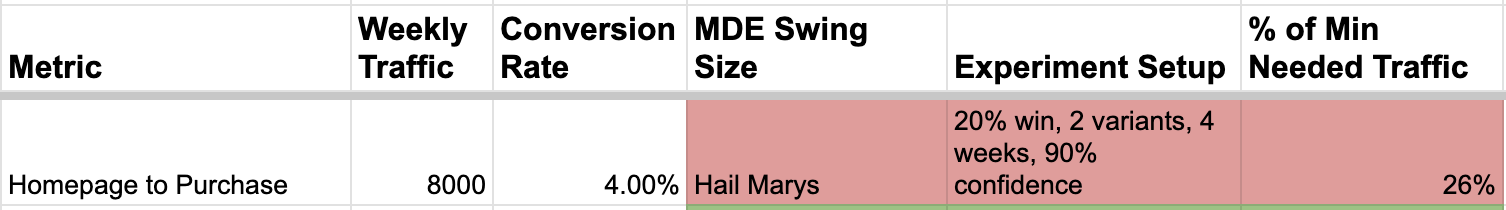

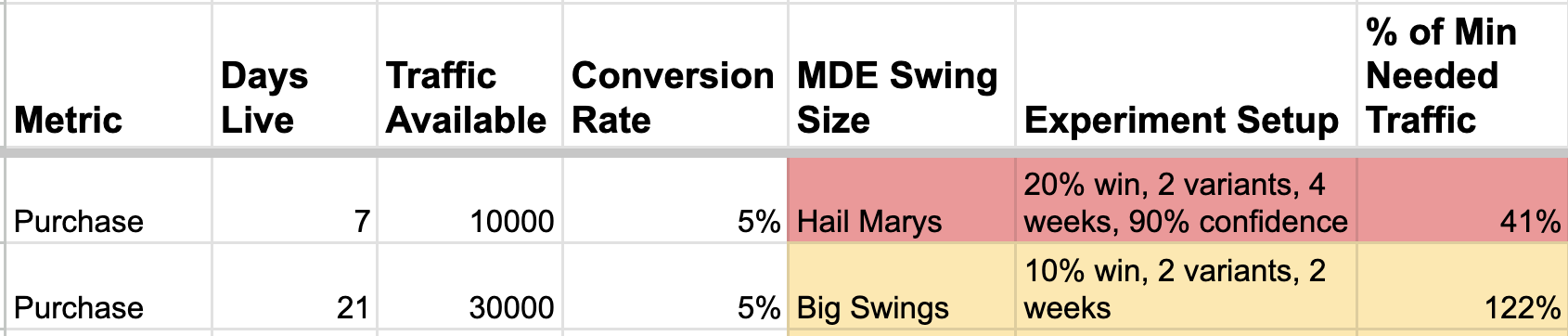

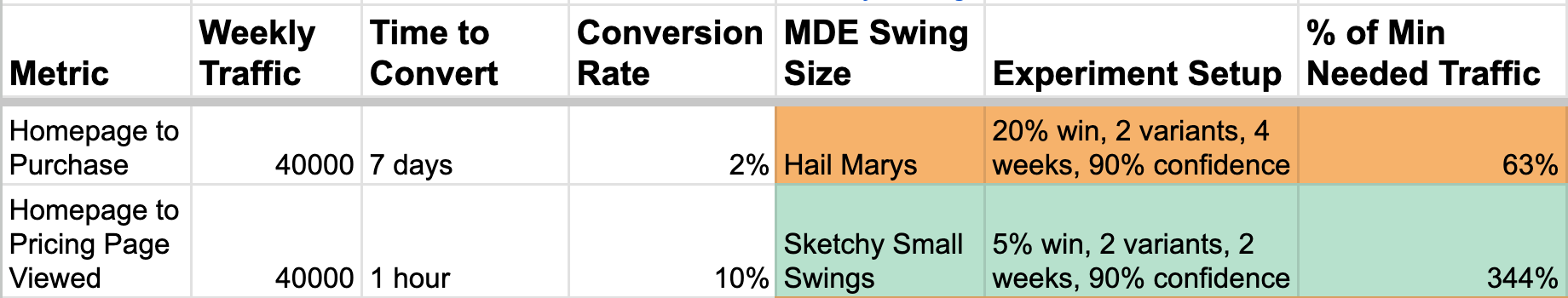

Consider an imaginary startup in turn considering funding a checkout optimization team.

Being well acquainted with power analysis, this startup gets its Minimal Detectable Effect - IE, how big of a swing would it need to.

Plugging their numbers into a swing size calculator, they learn that nothing less than a 20% win be detectable today.

Even 10% is a high bar to cross for winning experiments.

Gut Check Especially if you’re off by quite a bit, this is a chance to take a step back and ask whether the company has reached growth scale or not. It could be that there are plenty of obvious 0-1 tactics left. Not everything has to be an experiment.

In cases where experimentation remains the right choice, let’s find ways to adjust your experiment designs to be able to detect a 10% winner within a reasonable timeframe.

Part 2: Boosters

Things to try if you need to get just a little bit closer to get to stat-sig:

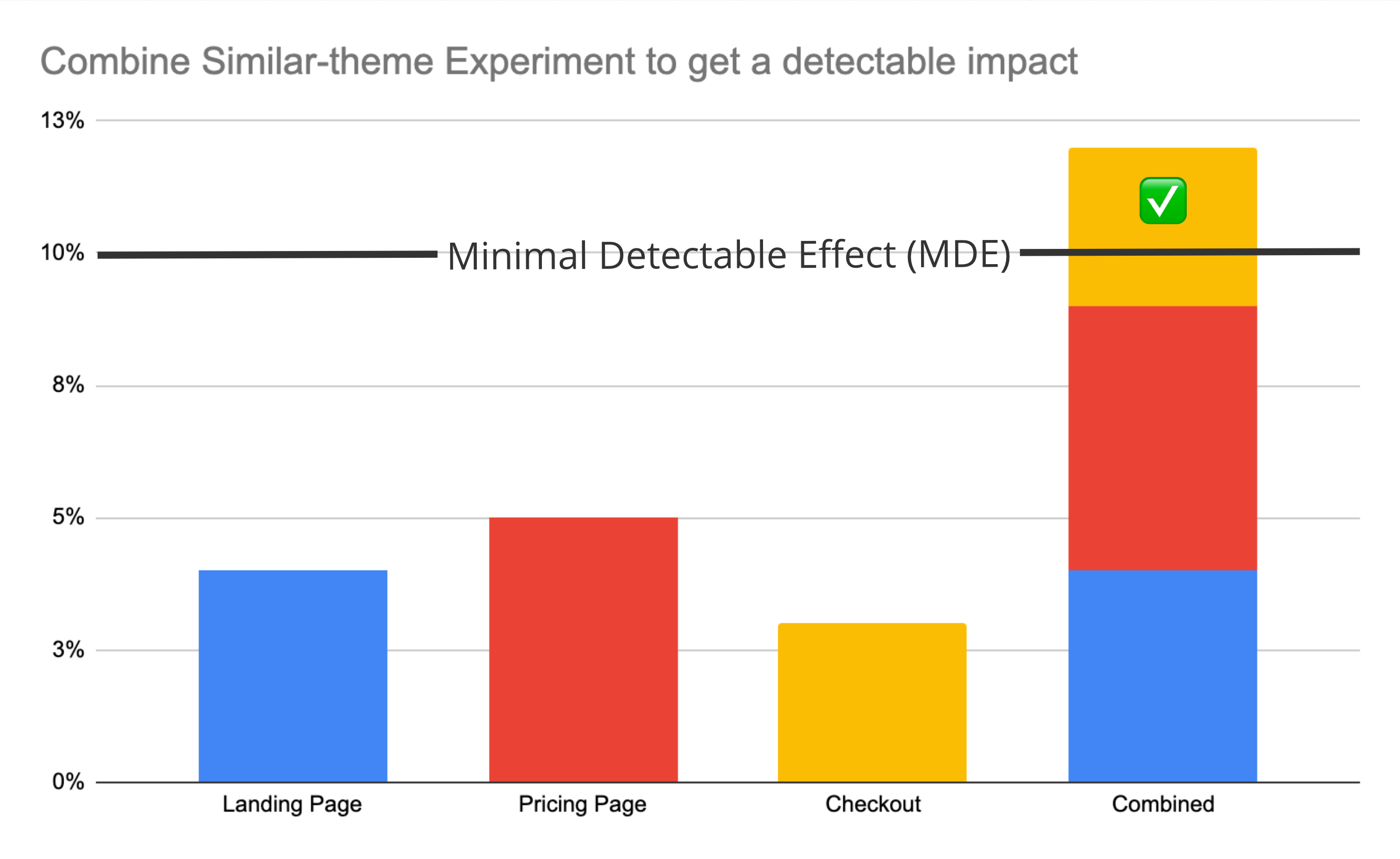

Bigger Bets: combine ideas together, merging by theme

The first thing to try is combining certain ideas with a common theme together. For example, if you believe emphasizing your transparent pricing will help conversion and are considering experiments to display your transparent pricing prominently on your homepage, during checkout, and in your cart abandonment emails.

Instead of running 3 experiments which might (for example) each move conversion by a bit, run them as a single “emphasize transparent pricing everywhere” mega-experiment so it has a better shot to hit the 10% detectable threshold you need.

The trade-off is reduced learning quality. When productionizing a batched win, it’s harder to tell which part of the change was actually effective. In the near term, this is tolerable - when the company gets to a larger scale and you revisit this theme, you can always tease out the underlying causes through follow-up experiments.

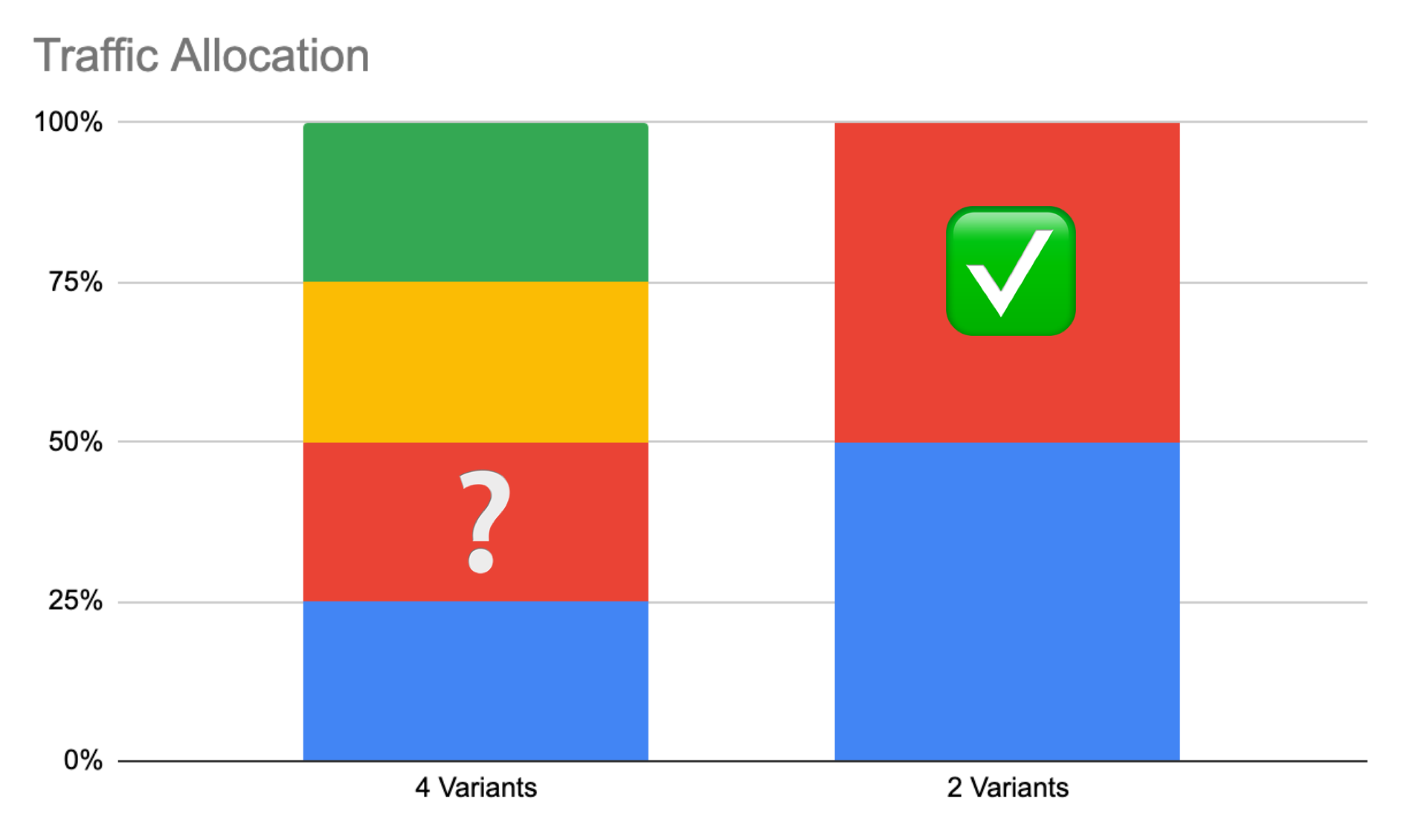

Best Foot Forward: Use fewer variants, A/B/C/D become A/B

You need a certain number of visitors to both your “winning variant” and “control” to determine the result. Every variant you add reduces the oxygen flow to your winning variant.

If you’re tight on traffic, stick to two variants.

The trade-off is, **this reduces your win rate, since you’re not getting to try as many options.

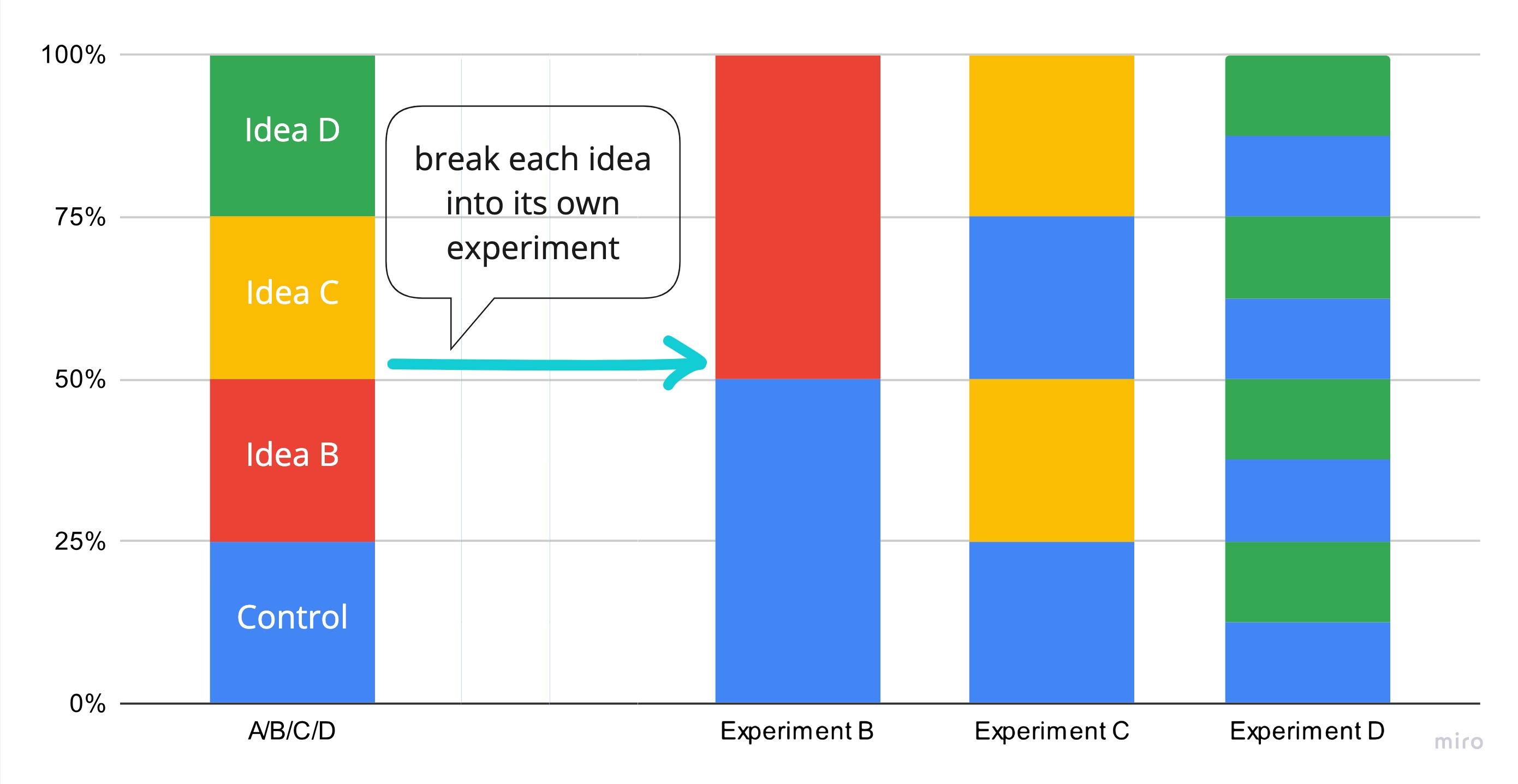

Run in Parallel: A/B/C/D becomes A/B, A/C, and A/D

We know by now that combining ideas together gives them the best shot at being sufficiently big winners. Some ideas, however, are dangerous enough to merit greater care.

Consider bodybuilding. You are probably fine combining “drink milk,” “eat raw eggs,” and “get good sleep” all at once, since these are relatively common approaches. However, if you decide to start injecting experimental supplements, you probably want to go one supplement at a time. If the side effects end up harmful, you want to be crystal clear on what is causing them.

The same is true for particularly sensitive experiments. Consider a test around “combatting high price perception.” **Various alternatives include a value-focused redesign of the pricing page, a free trial, and a price drop. **Since the latter two may be net-harmful to revenue, we should test them in isolation carefully.

Unlike with bodybuilding, testing in isolation does not require slowing down. Using modern experiment frameworks, all 3 of ideas can be safely tested at once, using parallel A/B tests (see chart).

Even better, as a side effect, you also gain directional evidence about how the ideas interact when they work together (IE, the free trial seems to work much better with the new redesign).

The trade-off is, running multiple experiments on the same surface area increases the burden on both engineering and analytics. For engineering, more complexity means more tests to reduce the potential for edge cases. For analytics, simultaneous experiments provide an extra require to inspect experiment interactions to avoid drawing false conclusions. When bottlenecked on experiment volume (versus eng or analytics throughput) this can be a worthwhile tradeoff.

Share Components on High-Throughput Surface Areas

[hat-tip to Taylor Adams]

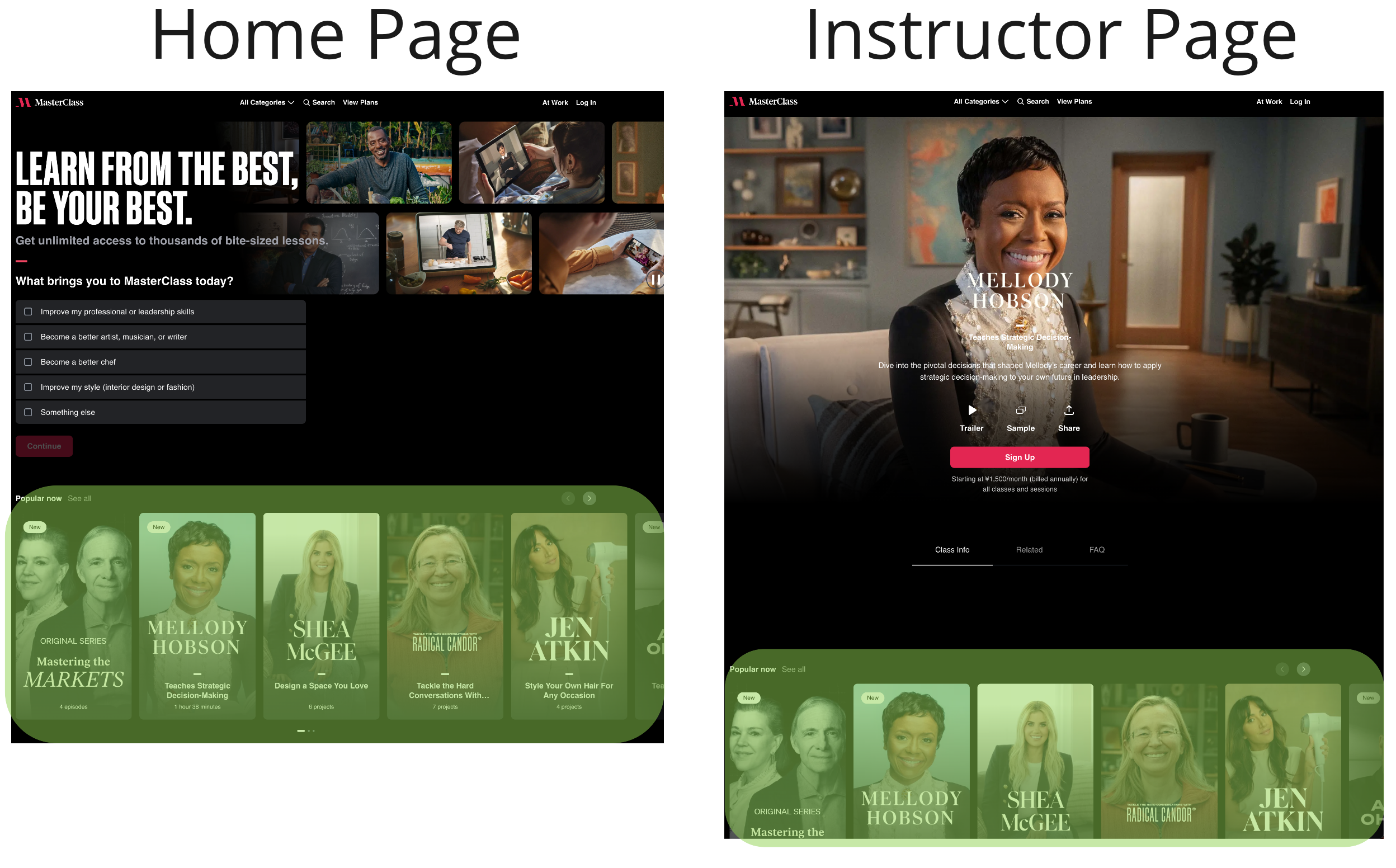

The place that has the most experimental power will generally be at the start of your checkout flow: it is seen by 100% of eventual purchasers, and converts relatively well. Your homepage is probably also a high-throughput surface area, but some customers may skip it and convert straight from other landing pages.

To get more power for top of funnel experiments, you can either (a) avoid custom landing pages and send almost all your traffic to the homepage or (b) share reusable components between your homepage and landing pages, and run experiments within those shareable components.

The trade-off of this approach constraints the amount of flexibility you can have on your other landing pages. Early on, it can be quite valuable to avoid constraining landing page formats, since that team needs to be taking its own big swings.

Run tests for longer: 7 days becomes 2-3 weeks

If you have more traffic, you get a larger sample size, which means you can detect smaller wins easier.

The trade-off is the likelihood you’ll get to see the experiment through. Especially at earlier stage companies, I rarely see the discipline to actually leave an experiment running longer than a couple of weeks. Inevitably, an executive will pop in and demand an update. “Trending positive?” they’ll say, “Great, let’s just ship it, it’s fine.” And it is fine, except now you’ve committed the cardinal sin of peeking, your likelihood of a false positive has gone up, and you have not truly “learned” anything that will help your experiment roadmap.

If you often find yourself shipping tests earlier than planned, consider switching to a non-frequentist (fixed-sample) methodology, such as Bayesian or Sequential statistics.

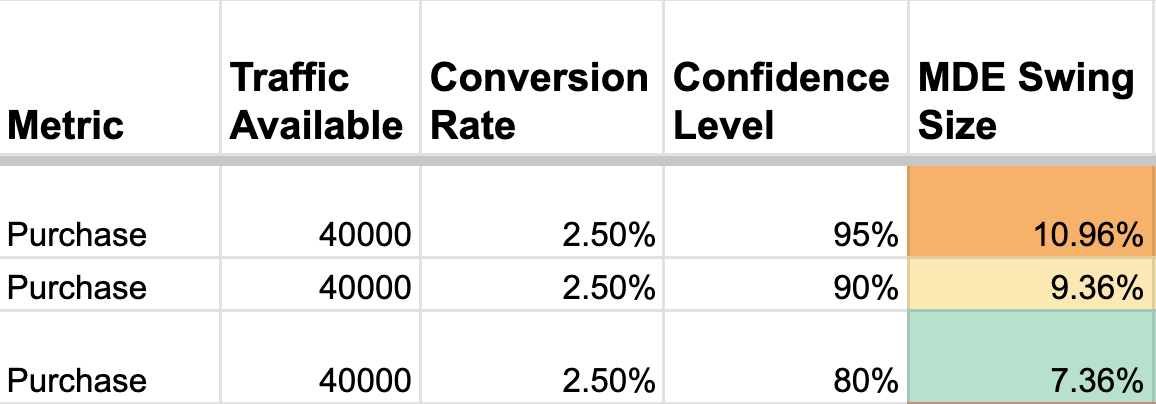

Get Comfortable with False Positives: p<0.05 becomes p<0.2

Another tolerable trade-off: in a world where a false positive is harmless, get comfortable setting your Type 1 Error tolerance (IE, how often can I live with a false positive) from its traditional a=0.05 (a 5% false positive) as high as a=.2 (a 20% false positive rate)

The trade-off is, you shouldn’t do this for risky or significant changes, such as a new pricing strategy. Also, realize that your ability to trust your learnings from experiments is decreased, since there’s a greater chance your “insights” are now coming from noise and not reality.

Buy Traffic

[hat-tip to Taylor Adams]

If the budget is available, you can always ask the paid marketing team to increase their spend during your experiment. A quick traffic boost can get you the numbers you need.

The trade-off is, newly-acquired prospecting paid traffic tends to be lower intent than your average visitor, so expect some conversion degradation (which may, in turn, make getting to stat-sig harder). Also, there’s probably a reason the paid marketing hasn’t increased their budget yet: the newly-acquired traffic is unlikely to be cost-efficient, and will likely burn money, so try not to pull this card too often.

Part 3: Desperate Times

When you’re an order of magnitude (>2x) away from stat-sig, there’s still a few (more aggressive) things to try:

Target a Proxy Metric

At Opendoor, our team’s job was to optimize conversion for people selling us their houses. However, a house sale actually closing took months and was not a common event, especially compared to a SAAS or eCommerce setup. Instead, we found a number of proxy metrics (offer viewed, etc) that we could target instead.

The trade-off is the new layer of indirection. Without being careful, it’s easy to get caught up in moving the proxy in a way that doesn’t help with your actual goal. For example, at Opendoor, shortening the purchase flow would result in more offers viewed, but fewer purchases at the end (since the offers would be less accurate).

To ensure the proxy metric doesn’t steer you astray, you can:

- Find or create higher-signal proxy metrics, such as a lead score model that can more accurately predict eventual conversion than merely the event itself taking place.

- Keep an eye on the impact your experiments are having on the true metric at least quarterly.

Run your Tests on the Paid Layer

[Hat-tip to Julian - I can’t for the life of me find the original quote, but here’s a good guide]

If you want to experiment with several headlines or images on your landing pages but don’t have enough traffic, you can test those very same headlines or images on paid marketing ads. The ones that perform best at the paid traffic level are reasonable candidates to do well on your marketing page.

The trade-off is that **this approach is limited in which parts of your product journey you can test.

Go Qualitative with Surveys, Paid Feedback and Session Recording

If you want to gain intuition for what users want - just ask them, or look for yourself!

There are several ways to get qualitative feedback about variants in your conversion journey:

1. Use a tool like hotjar.com

to ask a fraction of customers on the website to take a quick survey about their experience.

However, customers willing to do surveys are not always representative of your potential users.

2. Pay testers

on sites like UserTesting to go through your site (or even just designs iterations) and offer their feedback/see where they get stuck.

However, if you’re targeting wealthier customers or business purchasers, you may not get representative feedback.

3. Use screen recording tools

like Sprig or FullStory and personally watch the experience of tens of customers in your experimental variants.

However, it’s easy to get fixated on a specific issue that may not be representative or affect many customers.

Ideally, many of these approaches are often used during design, as a precursor to running an A/B test, but in a pinch, they can be used to in lieu of the quantitative tests.

YOLO - Just Make the Change

Ultimately, the simplest thing you can always do is just go ahead and make whatever change it is you believe in. So long as you are right often enough, you should start to see conversion starting to tick up over time.

Subscribe to Engineering Growth

Stay up to date on new essays and updates on Growth Engineering.

This approach also saves a decent amount of engineering effort, since you no longer need to spend eng effort on supporting more than one version of your site or product.

The trade-off is that **without the precision A/B testing, it’s that much harder to know which of your efforts are actually working, and which are neutral-to-harmful. Working pre-post puts you back in the old days of “half of my marketing efforts are wasted, but I don’t know which half.” At the end of the day, favoring conviction and best practices over experimentation is a reasonable approach, especially early on in a company’s lifetime.