Originally published as a guest blog post on interviewing.io. Thanks Aline!

“The new VP wants us to double engineering’s headcount in the next six months. If we have a chance in hell to hit the hiring target, you seriously need to reconsider how fussy you’ve become.”

It’s never good to have a recruiter ask engineers to lower their hiring bar, but he had a point. It can take upwards of 100 engineering hours to hire a single candidate, and we had over 50 engineers to hire. Even with the majority of the team chipping in, engineers would often spend multiple hours a week in interviews. Folks began to complain about interview burnout.

Also, fewer people were actually getting offers; the onsite pass rate had fallen by almost a third, from ~40% to under 30%. This meant we needed even more interviews for every hire.

Visnu and I were early engineers bothered most by the state of our hiring process. We dug in. Within a few months, the onsite pass rate went back up, and interviewing burnout receded.

We didn’t lower the hiring bar, though. There was a better way.

Introducing: the Phone Screen Team

We took the company’s best technical interviewers and organized them into a dedicated Phone Screen Team. No longer would engineers be assigned between onsite interviews and preliminary phone screens at recruiting coordinators’ whims. The Phone Screen Team specialized in phone screens; everybody else did onsites.

Why did you think this would be a good idea?

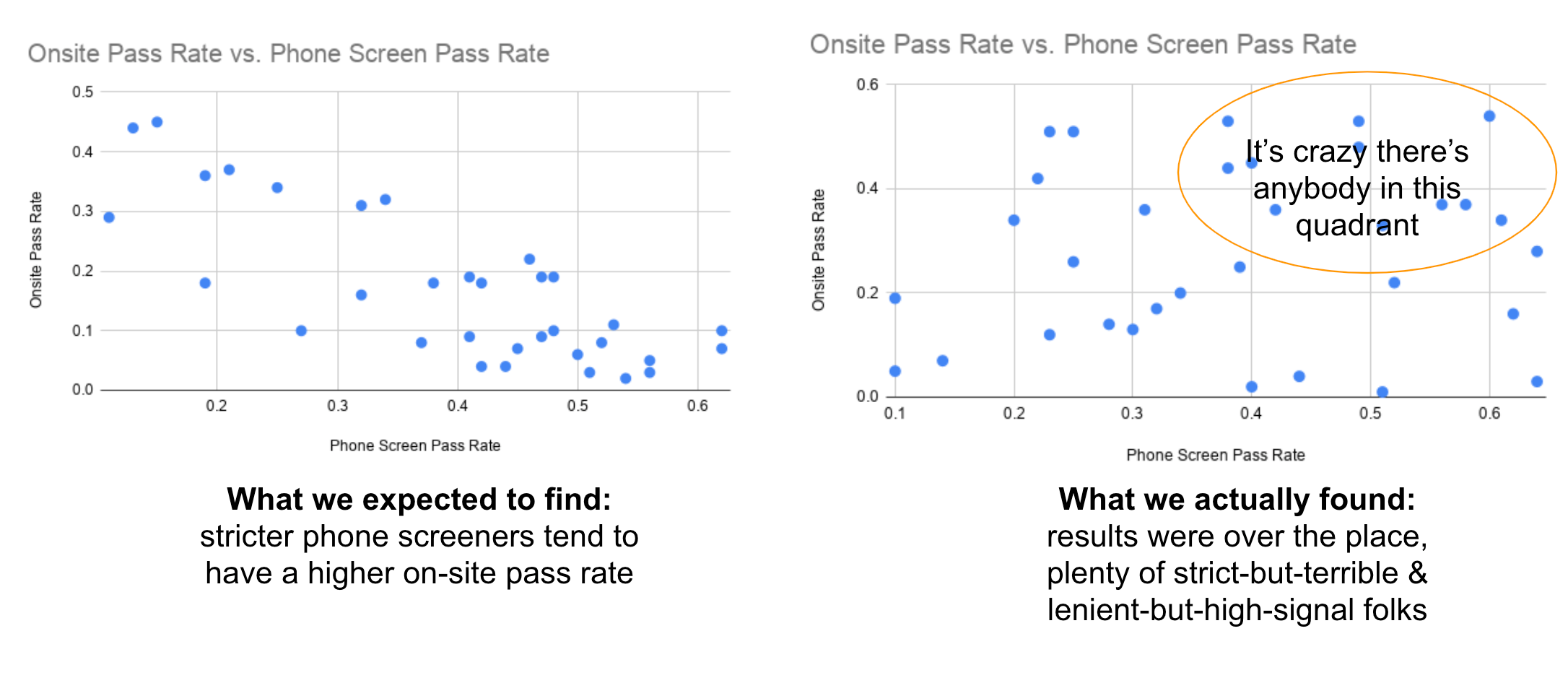

Honestly, all I wanted at the start was to see if I was a higher-signal interviewer than my buddy Joe. So I graphed people’s phone screen pass rate against how those candidates performed in their onsite pass rate.

Joe turned out to be the better interviewer. More importantly, I stumbled into the fact that a number of engineers doing phone screens performed consistently better across the board. They both had more candidates pass their phone screens and then those candidates would get offers at a higher rate.

Sample Data, recreated for Illustrative Purposes.

Sample Data, recreated for Illustrative Purposes.

These numbers were consistent, quarter over quarter. As we compared the top quartile of phone screeners to everybody else, the difference was stark. Each group included a mix of strict and lenient phone screeners; on average, both groups had a phone screen pass rate of 40%.

The similarities ended there: the top quartile’s invitees were twice as likely to get an offer after the onsite (50% vs 25%). These results also were consistent across quarters.

Armed with newfound knowledge of phone screen superforecasters, the obvious move was to have them do all the interviews. In retrospect, it made a ton of sense that some interviewers were “just better” than others.

A quarter after implementing the new process, the “phone screen to onsite” rate stayed constant, but the “onsite pass rate” climbed from ~30% to ~40%, shaving more than 10 hours-per-hire (footnote 2). Opendoor was still running this process when I left several years later.

You should too (footnote 3, footnote 4).

Starting your own Phone Screen Team

1. Identifying Interviewers (footnote 5)

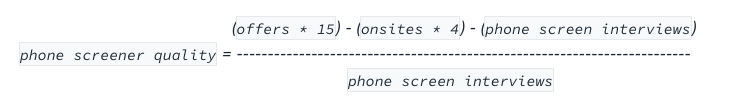

Get your Lever or Greenhouse (or ATS of choice) into an analyzable place somewhere, and then quantify how well interviewers perform. There’s lots of ways to analyze performance; here’s a simple approach which favors folks who generated lots of offers from as few as possible onsites and phone screens.

You can adjust the constants to where zero would match a median interviewer. A score of zero, then, is good.

Your query will look something like this:

| Interviewer | Phone Screens | Onsites | Offers | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accurate Alice | 20 | 5 | 3 | (45 - 20 - 20) / 20 = 0.25 |

| Friendly Fred | 20 | 9 | 4 | (60 - 36 - 20) / 20 = 0.2 |

| Strict Sally | 20 | 4 | 2 | (30 - 16 - 20) / 20 = -0.3 |

| Chaotic Chris | 20 | 10 | 3 | (45 - 40 - 20) / 20 = -0.75 |

| No Good Nick | 20 | 12 | 2 | (30 - 48 - 20) / 30 = -1.9 |

Ideally, hires would also be included in the funnel, since a great phone screen experience would make a candidate more likely to join. I tried including them; unfortunately, the numbers get too small and we start running out of statistical predictive power.

2. Logistics & Scheduling

Phone Screen interviewers no longer do onsite interviews (except as emergency backfills). The questions they ask are now retired from the onsite interview pool to avoid collisions.

Ask the engineers to identify and block off 4 hour-long weekly slots to make available to recruiting (recruiting coordinators will love you). Use a tool like youcanbook.me or calendly to create a unified availability calendar. Aim to have no more than ~2.5 interviews per interviewer per week. To minimize burnout, one thing we tried was to take 2 weeks off interviewing every 6 weeks.

To avoid conflict, ensure that interviewers’ managers are bought in to the time commitment and incorporate their participation during performance reviews.

3. Onboarding Interviewers

When new engineers join the company and start interviewing, they will initially conduct on-site interviews only. If they perform well, consider inviting them into the phone screen team as slots open up. Encourage new members to keep the same question they were already calibrated on, but adapt it to the phone format as needed. In general, it helps to make the question easier and shorter than if you were conducting the interview in person.

When onboarding a new engineer onto the team, have them shadow a current member twice, then be reverse-shadowed by that member twice. Discuss and offer feedback after each shadowing.

4. Continuous Improvement

Interviewing can get repetitive and lonely. Fight this head-on by having recruiting coordinators add a second interviewer (not necessarily from the team) to join 10% or so of interviews and discuss afterwords.

Hold a monthly retrospective with the team and recruiting, with three items on the agenda:

- discuss potential process improvements to the interviewing process

- review borderline interviews with the group to review together, if your interviewing tool supports recording and playback

- have interviewers read through feedback their candidates got from onsite interviewers and look for consistent patterns.

5. Retention

Eventually, interviewers may get burnt out and say things like “I’m interviewing way more people than others on my actual team - why? I could just go do onsite interviews.” This probably means it’s time to rotate them out. Six months feels about right for a typical “phone screen team” tour of duty, to give people a rest. Some folks may not mind and stay on the team for longer.

Buy exclusive swag for team members. Swag are cheap and these people are doing incredibly valuable work. Leaderboards (“Sarah interviewed 10 of the new hires this year”) help raise awareness. Appreciation goes a long way.

Also, people want to be on teams with cool names. Come up with a cooler name than “Phone Screen Team.” My best idea so far is “Ambassadors.”

Conclusion

There’s something very Dunder Mifflin about companies that create Growth Engineering organizations to micro-optimize conversion, only to have those very growth engineers struggle to focus due to interview thrash from an inefficient hiring process. These companies invest millions into hiring, coaching and retaining the very best sales people. Then they leave recruiting - selling the idea of working at the company - in the hands of an engineer that hasn’t gotten a lick of feedback on their interviewing since joining two years ago, with a tight project deadline on the back of her mind.

If you accept the simple truth that not all interviewers are created equal, that the same rigorous quantitative process with which you improve the business should also be used to improve your internal operations, and if you’re trying to hire quickly, you should consider creating a Technical Phone Screen Team.

FAQs, Caveats, and Pre-emptive Defensiveness

- Was this statistically significant, or are you conducting pseudoscience? Definitely pseudoscience. Folks in the sample were conducting about 10 interviews a month, ~25 per quarter. Perhaps not yet ready to publish in Nature but meaningful enough to infer from, especially considering the relatively low cost of being wrong.

- Why didn’t the on-site pass rate double, as predicted? First, not all of the top folks ended up joining the team. Second, the best performers did well because of a combination of skill (great interviewers, friendly, high signal) and luck (got better candidates). Luck is fleeting, resulting in a regression to the mean.

- What size does this start to make sense at? Early on, you should just identify who you believe your best interviewers are and have them (or yourself) do all the phone screens. Then, once you start hiring rapidly enough that you are doing about 5-10 phone screens a week, run the numbers and invite your best 2-3 onsite interviewers to join and create the team.

- What did you do for specialized engineering roles? They had their own dedicated processes. Data Science ran a take home, Front-End engineers had their own Phone Screen sub-team, and Data and ML Engineers went through the general full-stack engineer phone screen.

- Didn’t shrinking your Phone Screener pool hurt your diversity? In fact, the opposite happened. First, the phone screener pool had a higher percentage of women than the engineering organization at the time; second, a common interviewing anti-pattern is “hazing” - asking difficult questions and then rejecting somebody for “not even remembering about Kahn’s algorithm, lolz.” The best phone screeners don’t haze, bringing a more diverse group onsite.